Alcohol

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Alcohols)

This article is about the generic chemistry term. For the kind of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages, see Ethanol. For beverages containing alcohol, see Alcoholic beverage. For other uses, see Alcohol (disambiguation).

In chemistry, an alcohol is any organic compound in which a hydroxyl functional group (-OH) is bound to a carbon atom, usually connected to other carbon or hydrogen atoms.An important class are the simple acyclic alcohols, the general formula for which is CnH2n+1OH. Of those, ethanol (C2H5OH) is the type of alcohol found in alcoholic beverages, and in common speech the word alcohol refers specifically to ethanol.

Other alcohols are usually described with a clarifying adjective, as in isopropyl alcohol (propan-2-ol) or wood alcohol (methyl alcohol, or methanol). The suffix -ol appears in the IUPAC chemical name of all substances where the hydroxyl group is the functional group with the highest priority; in substances where a higher priority group is present the prefix hydroxy- will appear in the IUPAC name. The suffix -ol in non-systematic names (such as paracetamol or cholesterol) also typically indicates that the substance includes a hydroxyl functional group and so can be termed an alcohol, but many substances (such as citric acid, lactic acid or sucrose) contain one or more hydroxyl functional groups without using the suffix.

Simple alcohols

The most commonly used alcohol is ethanol, C2H5OH, with the ethane backbone. Ethanol has been produced and consumed by humans for millennia, in the form of fermented and distilled alcoholic beverages. It is a clear flammable liquid that boils at 78.4 °C, which is used as an industrial solvent, car fuel, and raw material in the chemical industry. In the US and some other countries, because of legal and tax restrictions on alcohol consumption, ethanol destined for other uses often contains additives that make it unpalatable (such as Bitrex) or poisonous (such as methanol). Ethanol in this form is known generally as denatured alcohol; when methanol is used, it may be referred to as methylated spirits ("Meths") or "surgical spirits".The simplest alcohol is methanol, CH3OH, which was formerly obtained by the distillation of wood and therefore is called "wood alcohol". It is a clear liquid resembling ethanol in smell and properties, with a slightly lower boiling point (64.7 °C), and is used mainly as a solvent, fuel, and raw material. Unlike ethanol, methanol is extremely toxic: one sip (as little as 10 ml) can cause permanent blindness by destruction of the optic nerve and 30 ml (one fluid ounce) is potentially fatal.[1]

Two other alcohols whose uses are relatively widespread (though not so much as those of methanol and ethanol) are propanol and butanol. Like ethanol, they can be produced by fermentation processes. (However, the fermenting agent is a bacterium, Clostridium acetobutylicum, that feeds on cellulose, not sugars like the Saccharomyces yeast that produces ethanol.) Saccharomyces yeast are known to produce these higher alcohols at temperatures above 75 F. These alcohols are called fusel alcohols or fusel oils in brewing and tend to have a spicy or peppery flavor. They are considered a fault in most styles of beer.[citation needed]

Simple alcohols, particularly ethanol and methanol, possess denaturing and inert rendering properties, leading to their use as anti-microbial agents in medicine, pharmacy and industry.[citation needed]

Nomenclature

Systematic names

In the IUPAC system, the name of the alkane chain loses the terminal "e" and adds "ol", e.g. "methanol" and "ethanol".[2] When necessary, the position of the hydroxyl group is indicated by a number between the alkane name and the "ol": propan-1-ol for CH3CH2CH2OH, propan-2-ol for CH3CH(OH)CH3. Sometimes, the position number is written before the IUPAC name: 1-propanol and 2-propanol. If a higher priority group is present (such as an aldehyde, ketone or carboxylic acid), then it is necessary to use the prefix "hydroxy",[2] for example: 1-hydroxy-2-propanone (CH3COCH2OH).The IUPAC nomenclature is used in scientific publications and where precise identification of the substance is important. In other less formal contexts, an alcohol is often called with the name of the corresponding alkyl group followed by the word "alcohol", e.g. methyl alcohol, ethyl alcohol. Propyl alcohol may be n-propyl alcohol or isopropyl alcohol depending on whether the hydroxyl group is bonded to the 1st or 2nd carbon on the propane chain.

Alcohols are classified into primary, secondary and tertiary, based upon the number of carbon atoms connected to the carbon atom that bears the hydroxyl group. Namely, the primary alcohols have general formulas RCH2OH; secondary ones are RR'CHOH; and tertiary ones are RR'R"COH, where R, R' and R" stand for alkyl groups. Ethanol and n-propyl alcohol are primary alcohols; isopropyl alcohol is a secondary one. The prefixes sec- (or s-) and tert- (or t-), conventionally in italics, may be used before the alkyl group's name to distinguish secondary and tertiary alcohols, respectively, from the primary one. For example, isopropyl alcohol is occasionally called sec-propyl alcohol, and the tertiary alcohol (CH3)3COH, or 2-methylpropan-2-ol in IUPAC nomenclature, is commonly known as tert-butyl alcohol or tert-butanol.

Common Names

| Chemical Formula | IUPAC Name | Common Name |

|---|---|---|

| Monohydric alcohols | ||

| CH3OH | Methanol | Wood alcohol |

| C2H5OH | Ethanol | Grain alcohol |

| C5H11OH | Pentanol | Amyl alcohol |

| C16H33OH | Hexadecan-1-ol | Cetyl alcohol |

| Polyhydric alcohols | ||

| C2H4(OH)2 | Ethane-1 ,2-diol | Ethylene glycol |

| C3H5(OH)3 | Propane-1 ,2,3-triol | Glycerin |

| C4H6(OH)4 | Butane-1 ,2,3,4-tetraol | Erythritol |

| C5H7(OH)5 | Pentane-1 ,2,3,4,5-pentol | Xylitol |

| C6H8(OH)6 | Hexane-1 ,2,3,4,5,6-hexol | Mannitol, Sorbitol |

| C7H9(OH)7 | Heptane-1 ,2,3,4,5,6,7-heptol | Volemitol |

| Unsaturated aliphatic alcohols | ||

| C3H5OH | Prop-2-ene-1-ol | Allyl alcohol |

| C10H17OH | 3,7-Dimethylocta-2,6-dien-1-ol | Geraniol |

| C3H3OH | Prop-2-in-1-ol | Propargyl alcohol |

| Alicyclic alcohols | ||

| C6H6(OH)6 | Cyclohexane-1 ,2,3,4,5,6-geksol | Inositol |

| C10H19OH | 2 - (2-propyl)-5-methyl-cyclohexane-1-ol | Menthol |

Etymology

| Look up alcohol in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

ال al is Arabic for the definitive article, the in English.

The current Arabic name for alcohol is الكحول al-kuḥūl, re-introduced from western usage.

kuḥl was the name given to the very fine powder, produced by the sublimation of the natural mineral stibnite to form antimony sulfide Sb2S3 (hence the essence or "spirit" of the substance), which was used as an antiseptic and eyeliner.

Bartholomew Traheron in his 1543 translation of John of Vigo introduces the word as a term used by "barbarous" (Moorish) authors for "fine powder":

- the barbarous auctours use alcohol, or (as I fynde it sometymes wryten) alcofoll, for moost fine poudre.

Physical and chemical properties

Alcohols have an odor that is often described as “biting” and as “hanging” in the nasal passages.The hydroxyl group generally makes the alcohol molecule polar. Those groups can form hydrogen bonds to one another and to other compounds (except in certain large molecules where the hydroxyl is protected by steric hindrance of adjacent groups[3]). This hydrogen bonding means that alcohols can be used as protic solvents. Two opposing solubility trends in alcohols are: the tendency of the polar OH to promote solubility in water, and of the carbon chain to resist it. Thus, methanol, ethanol, and propanol are miscible in water because the hydroxyl group wins out over the short carbon chain. Butanol, with a four-carbon chain, is moderately soluble because of a balance between the two trends. Alcohols of five or more carbons (Pentanol and higher) are effectively insoluble in water because of the hydrocarbon chain's dominance. All simple alcohols are miscible in organic solvents.

Because of hydrogen bonding, alcohols tend to have higher boiling points than comparable hydrocarbons and ethers. The boiling point of the alcohol ethanol is 78.29 °C, compared to 69 °C for the hydrocarbon Hexane (a common constituent of gasoline), and 34.6 °C for Diethyl ether.

Alcohols, like water, can show either acidic or basic properties at the O-H group. With a pKa of around 16-19 they are generally slightly weaker acids than water, but they are still able to react with strong bases such as sodium hydride or reactive metals such as sodium. The salts that result are called alkoxides, with the general formula RO- M+.

Meanwhile the oxygen atom has lone pairs of nonbonded electrons that render it weakly basic in the presence of strong acids such as sulfuric acid. For example, with methanol:

Alcohols can also undergo oxidation to give aldehydes, ketones or carboxylic acids, or they can be dehydrated to alkenes. They can react to form ester compounds, and they can (if activated first) undergo nucleophilic substitution reactions. The lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen of the hydroxyl group also makes alcohols nucleophiles. For more details see the reactions of alcohols section below.

As one moves from primary to secondary to tertiary alcohols with the same backbone, the hydrogen bond strength, the boiling point,and the acidity typically decrease.

Applications

Alcohols can be used as a beverage (ethanol only), as fuel and for many scientific, medical, and industrial utilities. Ethanol in the form of alcoholic beverages has been consumed by humans since pre-historic times. A 50% v/v solution of ethylene glycol in water is commonly used as an antifreeze.Some alcohols, mainly ethanol and methanol, can be used as an alcohol fuel. Fuel performance can be increased in forced induction internal combustion engines by injecting alcohol into the air intake after the turbocharger or supercharger has pressurized the air. This cools the pressurized air, providing a denser air charge, which allows for more fuel, and therefore more power.

Alcohols have applications in industry and science as reagents or solvents. Because of its low toxicity and ability to dissolve non-polar substances, ethanol can be used as a solvent in medical drugs, perfumes, and vegetable essences such as vanilla. In organic synthesis, alcohols serve as versatile intermediates.

Ethanol can be used as an antiseptic to disinfect the skin before injections are given, often along with iodine. Ethanol-based soaps are becoming common in restaurants and are convenient because they do not require drying due to the volatility of the compound. Alcohol is also used as a preservative for specimens.

Alcohol gels have become common as hand sanitizers.

Production

Industrially alcohols are produced in several ways:- By fermentation using glucose produced from sugar from the hydrolysis of starch, in the presence of yeast and temperature of less than 37 °C to produce ethanol. For instance the conversion of invertase to glucose and fructose or the conversion of glucose to zymase and ethanol.

- By direct hydration using ethylene (ethylene hydration)[5] or other alkenes from cracking of fractions of distilled crude oil.

Endogenous

Several of the benign bacteria in the intestine use fermentation as a form of anaerobic respiration. This metabolic reaction produces ethanol as a waste product, just like aerobic respiration produces carbon dioxide and water. Thus, human bodies inevitably contain some quantity of alcohol endogenously produced by these bacteria.Laboratory synthesis

Several methods exist for the preparation of alcohols in the laboratory.Substitution

Primary alkyl halides react with aqueous NaOH or KOH mainly to primary alcohols in nucleophilic aliphatic substitution. (Secondary and especially tertiary alkyl halides will give the elimination (alkene) product instead). Grignard reagents react with carbonyl groups to secondary and tertiary alcohols. Related reactions are the Barbier reaction and the Nozaki-Hiyama reaction.Reduction

Aldehydes or ketones are reduced with sodium borohydride or lithium aluminium hydride (after an acidic workup). Another reduction by aluminiumisopropylates is the Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction. Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation is the asymmetric reduction of β-keto-estersHydrolysis

Alkenes engage in an acid catalysed hydration reaction using concentrated sulfuric acid as a catalyst which gives usually secondary or tertiary alcohols. The hydroboration-oxidation and oxymercuration-reduction of alkenes are more reliable in organic synthesis. Alkenes react with NBS and water in halohydrin formation reaction. Amines can be converted to diazonium salts which are then hydrolyzed.The formation of a secondary alcohol via reduction and hydration is shown:

Reactions

Deprotonation

Alcohols can behave as weak acids, undergoing deprotonation. The deprotonation reaction to produce an alkoxide salt is either performed with a strong base such as sodium hydride or n-butyllithium, or with sodium or potassium metal.- 2 R-OH + 2Na → 2R-O−Na + H2

- E.g. 2 CH3CH2-OH + 2 Na → 2 CH3-CH2-O−Na + H2

- R-OH + NaOH <=> R-O-Na+ + H2O (equilibrium to the left)

The acidity of alcohols is also affected by the overall stability of the alkoxide ion. Electron-withdrawing groups attached to the carbon containing the hydroxyl group will serve to stabilize the alkoxide when formed, thus resulting in greater acidity. On the other hand, the presence of electron-donating group will result in a less stable alkoxide ion formed. This will result in a scenario whereby the unstable alkoxide ion formed will tend to accept a proton to reform the original alcohol.

With alkyl halides alkoxides give rise to ethers in the Williamson ether synthesis.

Nucleophilic substitution

The OH group is not a good leaving group in nucleophilic substitution reactions, so neutral alcohols do not react in such reactions. However, if the oxygen is first protonated to give R−OH2+, the leaving group (water) is much more stable, and the nucleophilic substitution can take place. For instance, tertiary alcohols react with hydrochloric acid to produce tertiary alkyl halides, where the hydroxyl group is replaced by a chlorine atom by unimolecular nucleophilic substitution. If primary or secondary alcohols are to be reacted with hydrochloric acid, an activator such as zinc chloride is needed. Alternatively the conversion may be performed directly using thionyl chloride.[1]

Alcohols may likewise be converted to alkyl bromides using hydrobromic acid or phosphorus tribromide, for example:

- 3 R-OH + PBr3 → 3 RBr + H3PO3

Dehydration

Alcohols are themselves nucleophilic, so R−OH2+ can react with ROH to produce ethers and water in a dehydration reaction, although this reaction is rarely used except in the manufacture of diethyl ether.More useful is the E1 elimination reaction of alcohols to produce alkenes. The reaction generally obeys Zaitsev's Rule, which states that the most stable (usually the most substituted) alkene is formed. Tertiary alcohols eliminate easily at just above room temperature, but primary alcohols require a higher temperature.

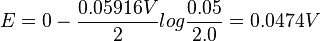

This is a diagram of acid catalysed dehydration of ethanol to produce ethene:

A more controlled elimination reaction is the Chugaev elimination with carbon disulfide and iodomethane.

Esterification

To form an ester from an alcohol and a carboxylic acid the reaction, known as Fischer esterification, is usually performed at reflux with a catalyst of concentrated sulfuric acid:- R-OH + R'-COOH → R'-COOR + H2O

Other types of ester are prepared similarly—for example tosyl (tosylate) esters are made by reaction of the alcohol with p-toluenesulfonyl chloride in pyridine.

Oxidation

Main article: Alcohol oxidation

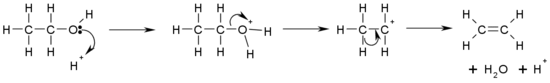

Primary alcohols (R-CH2-OH) can be oxidized either to aldehydes (R-CHO) or to carboxylic acids (R-CO2H), while the oxidation of secondary alcohols (R1R2CH-OH) normally terminates at the ketone (R1R2C=O) stage. Tertiary alcohols (R1R2R3C-OH) are resistant to oxidation.The direct oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids normally proceeds via the corresponding aldehyde, which is transformed via an aldehyde hydrate (R-CH(OH)2) by reaction with water before it can be further oxidized to the carboxylic acid.

Mechanism of oxidation of primary alcohols to carboxylic acids via aldehydes and aldehyde hydrates

Toxicity

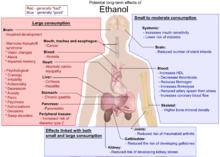

Main articles: Short-term effects of alcohol and Long-term effects of alcohol

Most significant of the possible long-term effects of ethanol. Additionally, in pregnant women, it causes fetal alcohol syndrome.

Other alcohols are substantially more poisonous than ethanol, partly because they take much longer to be metabolized and partly because their metabolism produces substances that are even more toxic. Methanol (wood alcohol), for instance, is oxidized to formaldehyde and then to the poisonous formic acid in the liver by alcohol dehydrogenase and formaldehyde dehydrogenase enzymes respectively; accumulation of formic acid can lead to blindness or death.[7] Similarly poisoning due to other alcohols such as ethylene glycol or diethylene glycol are due to their metabolites which are also produced by alcohol dehydrogenase.[8][9] An effective treatment to prevent toxicity after methanol or ethylene glycol ingestion is to administer ethanol. Alcohol dehydrogenase has a higher affinity for ethanol, thus preventing methanol from binding and acting as a substrate. Any remaining methanol will then have time to be excreted through the kidneys.[7][10][11]

Methanol itself, while poisonous, has a much weaker sedative effect than ethanol. Some longer-chain alcohols such as n-propanol, isopropanol, n-butanol, t-butanol and 2-methyl-2-butanol do however have stronger sedative effects, but also have higher toxicity than ethanol.[12][13] These longer chain alcohols are found as contaminants in some alcoholic beverages and are known as fusel alcohols,[14][15] and are reputed to cause severe hangovers although it is unclear if the fusel alcohols are actually responsible.[16] Many longer chain alcohols are used in industry as solvents and are occasionally abused by alcoholics,[17][18] leading to a range of adverse health effects

![E = E^{o}- {0.05916 V \over 2} log {[Cu^{2+}]_{diluted}\over [Cu^{2+}]_{concentrated}}\,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/d/8/6/d86e96c6f40bd81f2ce0a2fd8ec61031.png)